Sumbanese Ikat

Sumba, an Indonesian island east of Bali, is known for the rich figurative patterns of their ikat designs, encompassing humans, animals, plants, and Sumba’s native architecture, all of which reflect a rich cultural identity.

Sumbanese Warp Ikat Textiles: Culture, Transnational Trade, and Artistic Enterprise

Sumba is a small island within the Indonesian archipelago and the Sumbanese, like many of their neighbors (including the Javanese and Balinese), have distinctive, evolving, and flourishing artistic practices that encompass different textile techniques. Warp-ikat weavings with stylized figurative and abstract geometric designs are among the works that artists on the island produce. These textiles have proven popular beyond the Indian Ocean world, especially since the late twentieth century, with collectors and museums in Europe and the Americas acquiring works.

Warp ikat is an intricate and labor-intensive weaving technique. The warp threads are dressed on the loom and then wrapped and tied (often with dried palm leaves) to form patterns. When the partially-bound threads are removed from the loom and placed in the dye bath, the bound sections resist the dye. The newly patterned warps then go back on the loom and are woven into cloth. The ikat technique produces individualized designs with slightly blurred edges; these variations provide dynamism within the repeated patterns. Like batik, the precise origins of the ikat technique remain uncertain, however, the variations in resist-dye processes throughout Indonesia, and the Indian Ocean world, strongly suggest an evolution through trade and migration.

The textile designs contemporary weavers choose to create reflect Sumba’s culture and highlight colonial legacies as well as ongoing transnational exchange. As anthropologist and textile scholar Jill Forshee has argued “Through time, the region’s textiles have been transformed consistently in their designs and uses, in response to influences within, between, and beyond village realms” (Forshee, 2001, 4). A hinggi made in Kaliuda in 2016 demonstrates some of the ways in which artists draw inspiration from historic textiles as well as respond to the contemporary world.

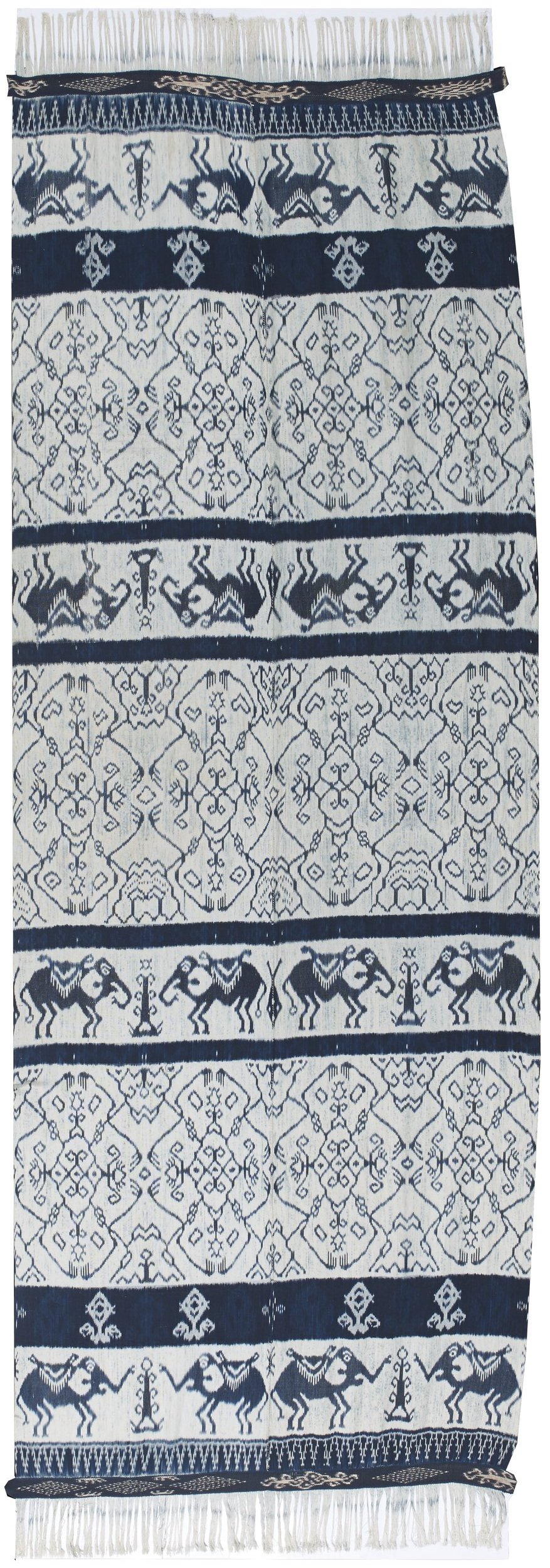

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 126 x 295 cm.

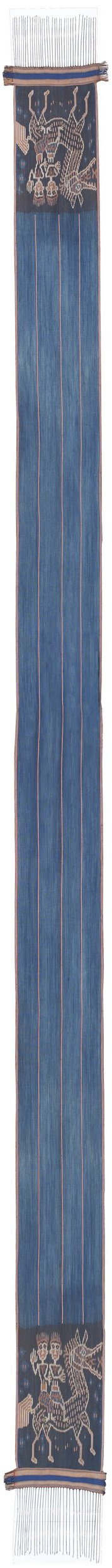

The color palette of blue, rust red, and natural cotton fiber as well as the mirrored striped design, with a wide central stripe featuring geometric patterns, bears a striking similarity to a hinggi produced during the mid-twentieth century. Within the stripes, both hinggis feature horse and rider patterns, although in the earlier work the same motif repeats in each reddish-orange stripe, whereas in the more recent example, each stripe (of the mirrored design) has unique motifs. Included among these individualized motifs are skull trees, a figural pair, houses, and dragons.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 254 cm.

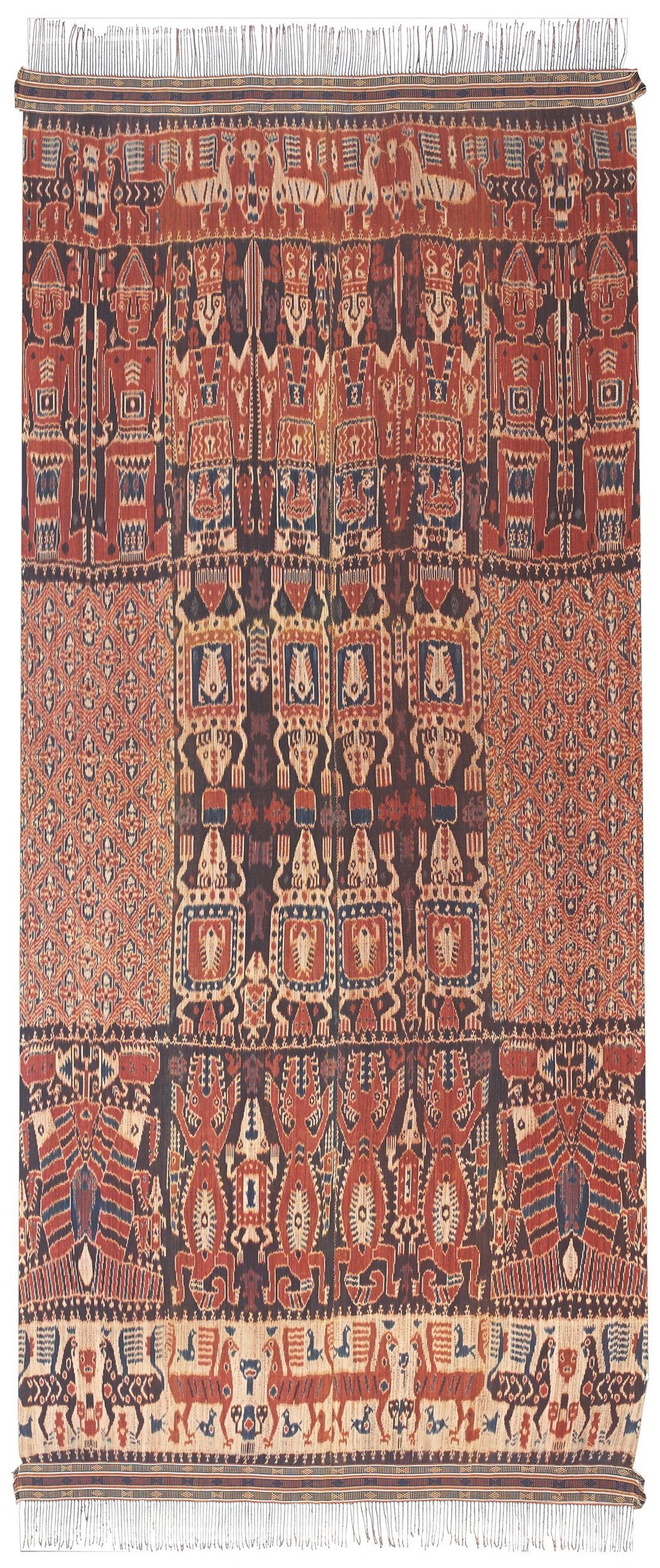

The profusion of distinct designs in the recently made work suggests the artist’s conscience attempt to meet the expectations of tourists and collectors with preconceived notions of Sumbanese life. The skull tree, no longer part of Sumbanese culture, remains ubiquitous in textiles as it suggests an ongoing connection to a “primitive” past. At the same time, the design demonstrates that Sumba was never the “primitive” or isolated place that travelers to the island (or adjacent locales such as Java or Bali) might have imagined. The dragon motif and geometric designs demonstrate the transcultural exchange of goods, ideas, and people. The dragon motif borrows from imported Chinese porcelain (such as this blue and white fifteenth century bowl in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection), and the geometric designs were potentially adapted from Indian patola (double ikat woven silks, such as the example below, from the V&A collection). The textile thus exemplifies the challenges artists face as well as the creativity and innovation with which they approach the myriad forces that impact their weaving practices.

Ceremonial Shoulder Cloth, made in Patan, Gujarat for export to Indonesia, 19th century. Silk, double ikat (patola), 80 x 244 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Patawang, about 1990-2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 127 x 303 cm.

Essay by Dr. Erica Warren; you can find more information about Dr. Warren on her website.

References

Jill Forshee, 1999. “Unfolding Passages: Weaving through the centuries in East Sumba” in Decorative Arts of Sumba. Amsterdam and Singapore: The Pepin Press, 31-51.

Jill Forshee, 2001. Between the Folds: Stories of Cloth, Lives, and Travels from Sumba. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Jill Forshee, 2012. “Rambu Pakki and Rambu Tokung: Pau, Sumba, Indonesia” in Weavers’ Stories: From Island Southeast Asia, Roy Hamilton ed. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Art at UCLA.

John Guy, 1998. Woven Cargoes: Indian Textiles in the East. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc.

Brigitte Khan Majlis, 2007. The Art of Indonesian Textiles: The E.M. Bakwin Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. New Haven: The Art Institute of Chicago and Yale University Press.

An artist wrapping and tying warp threads to prepare them for dyeing. A pattern on paper below the warps helps guide the binding process.

Dyed warps on the loom, ready to be woven.

A Sumbanese home with a high-peaked roof and wide veranda.

Bowl, made in China, 1425-35 (during the reign of Ming emperor Xuande. Porcelain, painted in underglaze blue, 27 cm (diameter).

Textile trade in the Indian Ocean world garnered note from Europeans as early as the end of the fifteenth century, however the textiles, through their designs and methods of facture (as well as radiocarbon dating), tell a story of exchange long predating accounts written from the colonial perspective. Some scholars, such as Brigitte Khan Majlis and John Guy, have argued that Indian textiles were formative in shaping Indonesia’s textile artists. Guy, a curator specializing in South and Southeast Asian Art reports that “Dutch [East India] Company officials observed that the Javanese, major buyers of both patola and fine-quality painted cottons, were more interested in the degree to which the designs conformed to local taste than in the fineness of thread and tightness of weave” (Guy, 1998, 87). Intriguingly, this statement reveals that the trade relationship between India and Indonesian responded to cultural particularities, and that the narrative of a singular directional influence (Indian textiles shaping Indonesian artists’ works), produces a reductive and limited picture of the artistic interplay that occurred.

Taking into account the uncertain origins of ikat, it is difficult to assert the precise manner in which textiles functioned as tools for transmitting knowledge, however, the sheer quantity of them, their myriad uses, and their movement are certain and significant. Forshee acknowledges this, asserting “Infinite complications enter any discussion of motifs used in Sumba and inevitably involve the elusive nature of meanings attributed to pictures. While imagery in Sumbanese fabrics reflects historical circumstances involving regional and global influences, designs also arise from instances of individual choice and creativity that are impossible to isolate” (Forshee, 2001, 37). These individual choices surface when comparing ikat textiles that have similar motifs such as two hinggis that both feature Dutch Queen Wilhelmina.

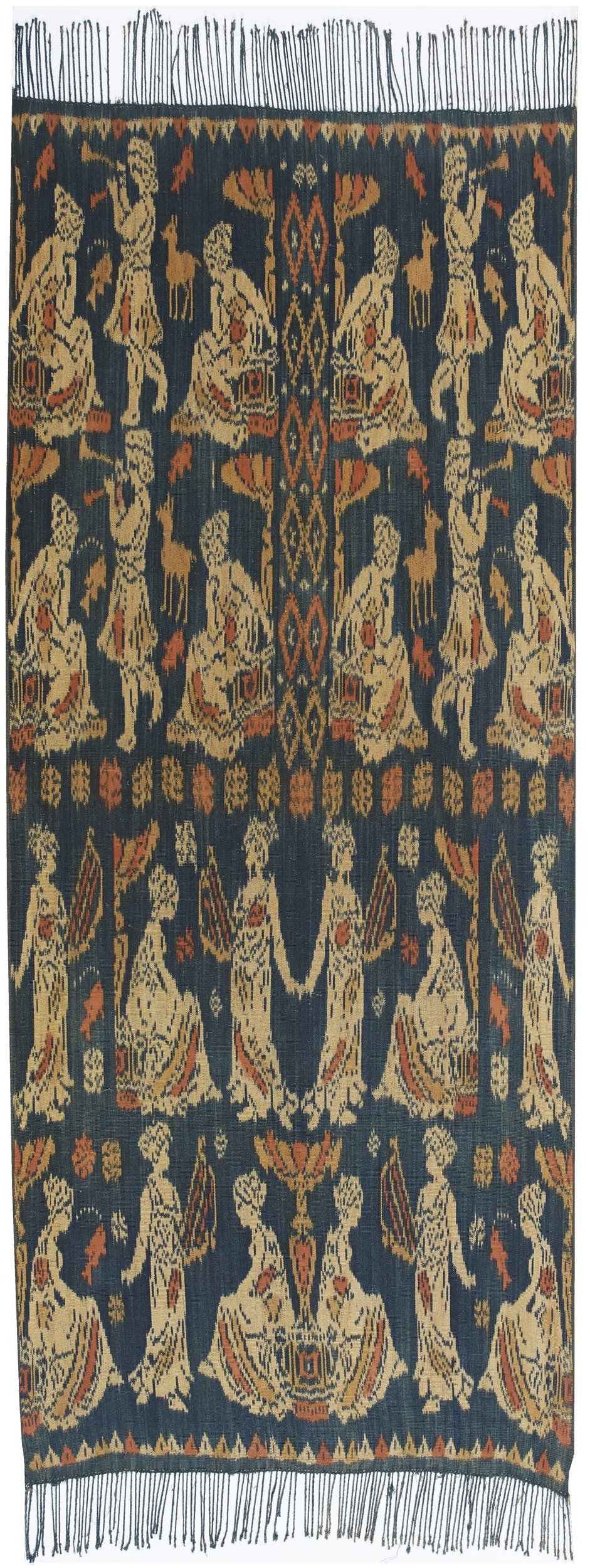

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Patawang, about 1960-1970. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 131 x 308 cm.

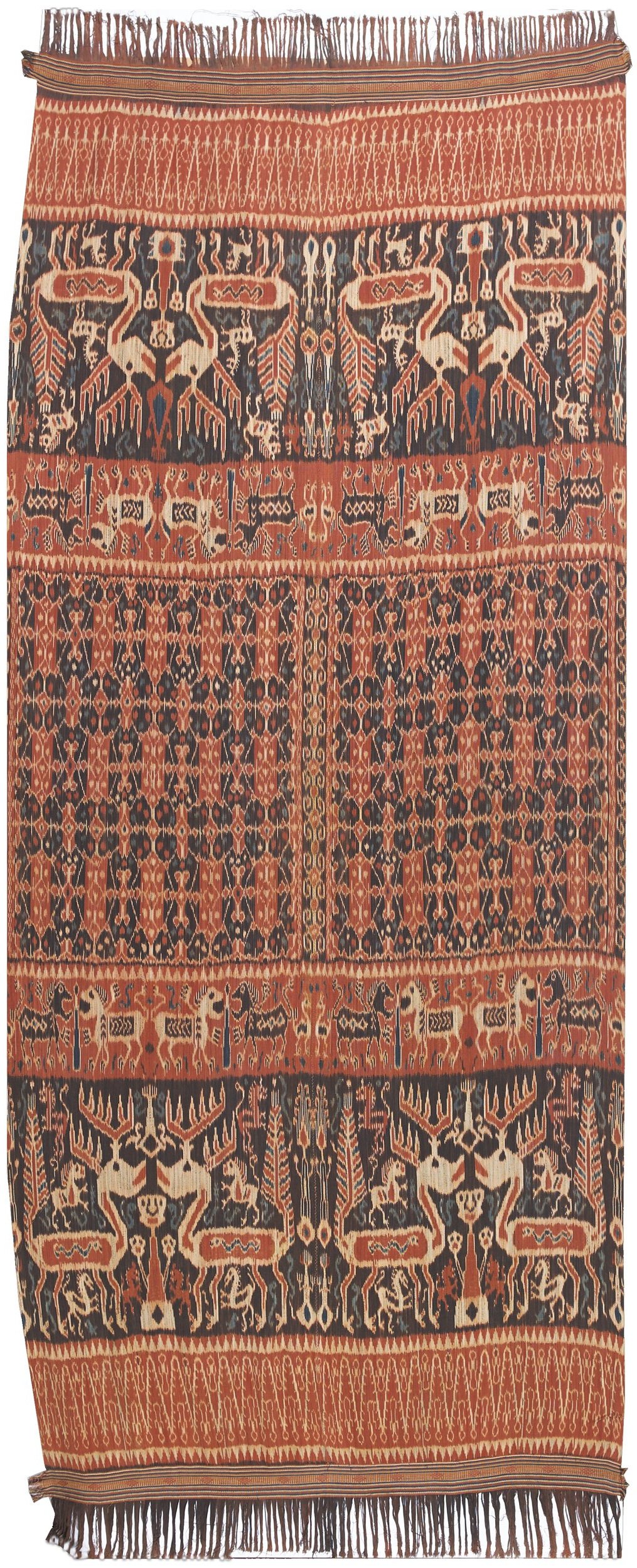

Woven in Patawang, but about thirty years apart, they clearly follow a shared design that incorporates Dutch royal symbols, including the queen as well as rampant and addorsed lions, into a Sumbanese aesthetic vocabulary. In both examples, the weaver portrays Queen Wilhelmina in a manner similar to the Sumbanese tau figure (a forward facing figure, sometimes depicted with interior anatomical structures), as featured in a blue and white hinggi from Dr. Indriati’s collection. Both Queen Wilhelmina hinggis were made after the end of Dutch colonial rule and demonstrate the persistent impact of colonialism in Indonesia. In the more recent example, the artist has further stylized and abstracted the animal forms, and the lions that border the central geometric pattern have taken on the appearance of griffins. Similarly, the queen has taken on a more menacing visage, her brow furrowed, a gesture mimicked in the arch above her head, suggesting a contemporary reappraisal of the past.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Rende, about 2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 127 x 315 cm.

Dr. Indriati’s Ikat Collection

Hinggi Kombu Pataduku Ayam, produced in Kaliuda, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 119 x 275 cm.

Hinggi Kombu pataduku kupu-kupu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 128 x 312 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1960. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 306 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Pahudur, produced in Kaliuda, about 1950. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 255 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1970. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 320 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1960. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 90 x 250 cm.

Lawu Hikung Hemba, produced in Pau, about 1990. Cotton, natural dye, 68 x 123 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Andungu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 124 x 305 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Garuda, produced in Kaliuda, 1952-1955. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 130 x 320 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 320 cm

Selendang Pasangan Hinggi Kombu Garuda, produced in Kaliuda, 1952-1954. Cotton, ikat, natural dye.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1960. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 153 x 310 cm.

Hinggi Kombu with Garuda Bird, produced in Kaliuda, about 2008. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 121 x 325 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 126 x 295 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 254 cm.

Hinggi Kombu with Queen Wilhelmina and King Hendrix, produced in Kaliuda, about 1940. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 117 x 274 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kaliuda, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 123 x 288 cm.

Halenda, woven by the Sawu people in Melolo, about 1970. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 72 x 192 cm.

Halenda, woven by the Sawu people in Melolo, about 1970. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 75 x 201 cm.

Halenda, woven by the Sawu people in Melolo, about 1970. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 281 x 193 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Rende, about 1970-1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 149 x 293 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Rende, about 1970-1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 163 x 278 cm.

Hinggi, produced in Rende, about 1980-1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 154 x 261 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Rende, about 1980-1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 123 x 265 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Rende, about 1980-1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 117 x 276 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Rende, about 2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 127 x 315 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Rende, about 1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 117 x 317 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Rende, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 110 x 254 cm.

Hinggi Halinggi, produced in Rende, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 94 x 282 cm.

Rohu Banggi, produced in Rende, about 1970. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 33 x 632 cm.

Lawu Pahudur, produced in Patawang, about 2010. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 65 x 149 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Patawang, about 1960-1970. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 131 x 308 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Patawang, about 1990-2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 127 x 303 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Warinding, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 108 x 267 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Kapunduk, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 122 x 298 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Palindi, about 1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 95 x 286 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Palindi, about 1980. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 84 x 315 cm .

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kanatang/Kambera, about 1970-1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 145 x 360 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kanatang, about 1980-1990. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 185 x 384 cm.

Halenda Hikung Hemba, produced in Kanatang, about 1970-1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 58 x 258 cm.

Halenda Hikung Hemba, produced in Kanatang, about 1970-1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 56 x 276 cm.

Lawu Kaworu Pakambuli Huoma, produced in Kanatang, about 2000. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 128 x 150 cm.

Lawu Kaworu Hemba Hita, produced in Kanatang, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 64 x 156 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Hondu Kihil, produced in Kambera-Kanatang, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 115 x 295 cm.

Hinggi Kumbu, produced in Kambera, about 1970. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 124 x 280 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kambera, about 1920. Silk, ikat, natural dye, 114 x 278 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kambera, about 1930. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 142 x 346 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kambera, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 127 x 455 cm.

Hinggi Kombu, produced in Kambera-Kanatang, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 120 x 338 cm.

Lawu Dari Janggamangu, produced in Kambera, about 1950. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 62 x 182 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Patola Hudaranggarara, produced in Kambera, about 1980. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 117 x 458 cm.

Hinggi Kombu Hondu Kihil, produced in Mauliru-Kambera, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 128 x 309 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Palamarung, Kambera, about 2016. Cotton, ikat, natural dye, 99 x 300 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu, produced in Kodi, Homba Karimpit, about 1980. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 134 x 304 cm.

Hinggi Kaworu Pahudur, produced in Kodi, about 1970-1980. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 97 x 277 cm.

Selendang Pahudur Bara, produced in Lamboya, about 1980. Hand spun cotton, ikat, natural dye, 92 x 280 cm.

Weaving in progress

In this image, a weaver works on finishing the checked selvage of an ikat textile. The colors in the selvage mirror those used in the ikat design, but the weaver uses uniform colors for the selvage warps to create a linear, geometric pattern.

“ . . .external influences as well as political and cultural changes have been interesting sources of new patterns incorporated in Sumba textiles.”

— Dr. Etty Indriati